Shabbat Va-yeitzei 5782

You can listen to Rabbi Deborah's sermon or read it below:

There’s this category of thing you’ve always known and therefore never actually checked to see if its true. You know, like the idea that you lose most of your body heat through your head, or that Vikings had horns on their helmets, or that fortune cookies are Chinese food, or that lemmings jump off cliffs, or that people really thought JFK was saying I am a donut when he said "Ich bin ein Berliner", or that there are 4 matriarchs in biblical tradition…

Like so many things we are just used to seeing and knowing and don’t really think to question, there’s often little reason why we ought to think about anyone other than Sarah, Rebekah, Leah, and Rachel. That’s who is in our prayer book and we’re in the midst of their stories in our Torah cycle, we’ve heard of Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah’s love, and this week’s portion, immediately after the part read by phoenix, is the beginning of the story of Leah and Rachel, the sisters and wives of Jacob.

But, as explained in this week’s portion, they weren’t the only mothers of Jacob’s children. Jacob’s children had four mothers, Rachel and Leah, and Bilhah and Zilpah- their handmaidens. They gave birth to 4 of Jacobs sons, that’s ⅓ of the tribes of Israel, but many of us have never heard of them.

The story of Bilhah and Zilpah is the original handmaid’s tale, the story that gives rise to the imagery that Margaret Atwood so evocatively explores in her books and their subsequent tv series. The imagery of how handmaids give birth in her books and tv show is drawn directly from the bible.It’s not a very easy story to hear, but it is an important one.

Bilhah and Zilpah are slave women and they live in the house of Laban. He gives them to his daughters, and in turn they give them to their husband, in a strange competition to see who can triumph over the other by bearing more children for Jacob.

What must it have been like for these two women, probably not so different in age to the women they served, to be treated in this way? They were passed around the home they served in, their bodies were not their own, they were forced to bear children. How young were they when they came to live in the house of this man?

What happens when we ask questions about these women? What happened to them? Some describe them as concubines, having served their role as womb slaves, they continue to be used to meet the physical needs of their master Laban.

A few chapters on from the birth stories of this week’s parasha, we learn more about Bilhah’s subsequent life. It’s a verse that according to the Talmud, we should not translate in public reading- it is simply described euphemistically as the incident with Reuben, and it’s not easy to hear. The verse tells of an encounter between Bilhah, and Reuben, Jacob’s son with his wife Leah.

Even without the Talmud’s signposting, the text contains details that suggests there is more going on in the verse than initially meets the eye.

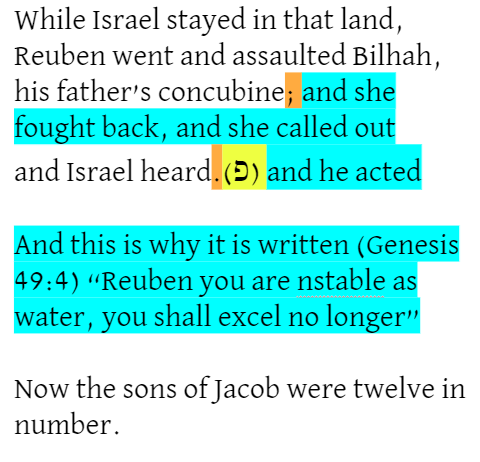

The first indicator is a letter pey in brackets in the middle of the sentence.

This symbol indicates the beginning of a new open portion, represented in a scroll by beginning a new line within the text. Though there is a portion break, it isn’t accompanied by a break between verses as would be expected. In fact, its right in the middle of a verse. The Masoretes who divided the continuous text into sections thus created a literal empty space within the narrative, perhaps indicating that there is more text within the verse that once belonged in that gap.

The strange portion break isn’t the only indicator that something isn’t quite right in this verse because the cantillation mark Etnachta (a small wishbone shape) also appears twice in Genesis 35:22.

This is unusual because Etnachta is a sign that ordinarily only occurs once, and it separates a verse into two halves. In this case where it appears twice, it has the effect of making it seem like there is a missing second half of a verse that follows the statement that Reuben lay with Bilhah, and thus a missing prelude to the words va’yishma Yisrael, ‘and Israel heard’.

Noting these peculiarities in the text led me to question what it is about the incident with Reuben that means this verse cannot be translated during a public reading when the masoretic markings appear to be drawing attention to the verse rather than suggesting it is skimmed over.

What happened?

Although the verse is most commonly translated as ‘he lay with’, if that was the case then the text would read va’yishkav im Bilhah. Instead, it reads et Bilhah, which puts Bilhah into a passive mode, suggesting that the lying was done to her rather than with her. Though the rabbis of the Talmud spend much time suggesting that Reuben simply ruffled the bedsheets, Jacob’s reaction later in Genesis in removing from Reuben the special blessings of the first born son cement the seriousness of Reuben’s actions.

Why can’t it be read in shul? Because it casts Reuben in a terrible light,the first born son is an abuser, the potential damage to Jacob’s household is enormous, and it reflects a wider tendency to look aside when confronted by such abuses- or to worry more about the impact on others than on the victim. Or could it be that there was a reluctance to read it in public because people behaved, and still behave like this, and because nobody wanted to be the one to call out powerful people for their actions, to say you can’t actually do this to someone?

What’s missing in the text of Genesis is any sense of what Bilhah experiences. She has been used first as a slave by Laban, then by Rachel, then handed as a womb-slave to Jacob, and now violated by his son. The womanist bible scholar Wil Gafney says that ‘Bilhah represents the woman who has had more than one abusive relationship, the woman who has been assaulted by more than one perpetrator, the woman who has been betrayed by women and men, who has never known anyone to value her for more than what they think about her body in part or the whole. And Bilhah represents the woman who survives her abuse.’

Bilhah doesn’t speak in the text that we have, but I when I studied this text I wanted to suggest there is an opportunity for us to find Bilhah’s voice in the verse and create a piece of modern midrash, one that might mean we too as readers are not complicit in the further confining Bilhah to the world of her trauma. What if we can find within this story a call to action?

The first Etnachta in the verse falls immediately after her assault. It means that it appears there is a missing second part to the verse.

What if we were to imagine what came next…

While Israel stayed in that land, Reuben went and he assaulted Bilhah, his father’s concubine; and she fought back. She called out

…and Israel heard, and he acted. (פ)

”Unstable as water, you shall excel no longer… You brought disgrace” (Genesis 49:4)

—---

Bilhah called out, and when she did, Israel heard. After all this time, she was heard, and perhaps this was the start of her journey out of this cycle of abuse, to the moment when she is listed amongst the matriachs in genesis 46.

I am particularly taken by the possibilities for us as inheritors of Jacob’s title to explore what ‘va’yishma Yisrael’ might mean in our society. In the midrash I imagine it as Jacob’s sensitivity to the cry of another, particularly one whose oppression he was once complicit in.

For us too, va’yishma Yisrael can be a call to confront the violations and transgressions within our own communities that we too once overlooked, and to act, as Jacob did, to ensure that those responsible are held to account. It also means we need to know what to do when we hear someone call for help- where to signpost them and how to notice the signs of abuse. To onlookers at the time, Jacobs just looked like an ordinary household, but it was a place of violation and harm.

This Shabbat Jewish Womens Aid has asked all of the communities in the UK to have an open conversation about domestic abuse and sexual violence. These aren’t easy topics, like the incident with Reuben there is huge social pressure to avoid these conversations, especially if perpetrators hold power. But we have to talk about it, because it happens, and it happens in our communities and in our families too.

Talking about real life experiences, understanding how abuse takes root, and knowing how to help each other, these are vital things. Like Bilhah and Zilpah’s stories, there are others in our community hiding in plain sight.

Learning how to hear their experiences can teach us how to hear others too. We cannot take the Talmud’s approach, and suggest that the way we act when we hear of these things is to avoid conversation, if we dream of a world where those who have been harmed can find safety, then it is conversations, learning and acting on what we hear that will help those who need it find their voices too.

-

Jewish Women's Aid

DOMESTIC ABUSE HELPLINE:

0808 801 0500

SEXUAL VIOLENCE SUPPORT LINE:

0808 801 0656

Support and advice for Men https://mensadviceline.org.uk/

NHS advice https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/healthy-body/getting-help-for-domestic-violence/